As I mentioned in my first post on this topic, wading into the arena of sensitivity readers immediately had me feeling as though I’d bitten off a bit more than I could chew. I am by no means positioning myself as an expert on this topic, and will continue to encourage you to check out the work of folks like Patrice Caldwell, Dhonielle Clayton, and Jennifer Baker, as well as everyone over at We Need Diverse Books as they’ve been hugely helpful to me wrapping my head around some of this.

As always, I hope to help us wade through these issues together, bringing along my unique perspective as an author and onetime publishing professional and my continued curiosity about how we can make book publishing better. Onward!

As I parsed through the controversy around sensitivity readers, I found myself sorting the arguments into two buckets: the bad faith hand-wringing and the thoughtful, legitimate critique. Of course, there was some crossover, but I think most people generally fell on one side or the other of this debate.

I should say that, of course, this all my personal opinion and I’m not here to speak for anyone or censor them (for God’s sake). I’m including lots of links here, so do feel free to go down the rabbit hole and make up your own mind.

My own evolution on the topic

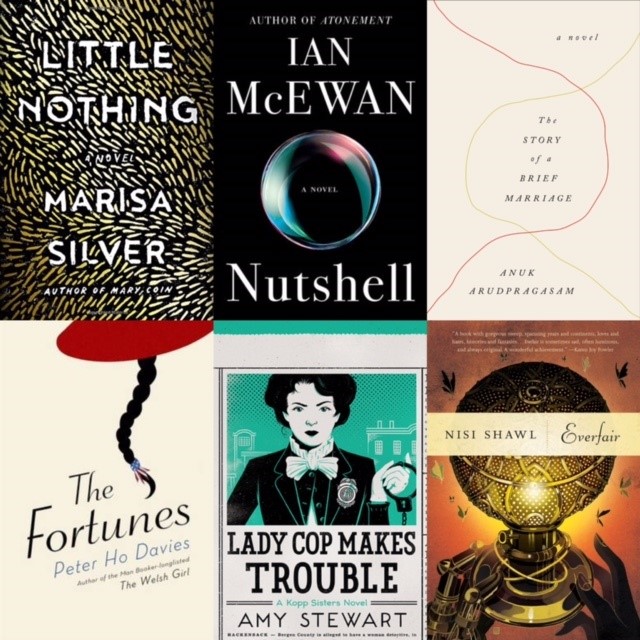

I confess that when sensitivity readers first became a widely-used practice (2015-ish), I was skeptical of it. I confess having my own instinctive defensiveness on the topic; which in retrospect seems like the fear and fragility many white writers I have when we think of being called out for stereotyping or being unintentionally racist. In their excellent treatise Writing the Other Nisi Shawl and Cynthia Ward call this the “liberal dread of the racist label”.

Knowing what I do about publishing, I also worried that use the practice was a band-aid to deal with its inherent racial biases and systemic issues, which were first given some solid data by the Lee & Lowe study that came out around that same time. Interesting, I think this duality pretty well reflects the two sides of this argument. I’ve evolved a great deal on the topic, and I’ll get to that in a future video

But today I want to present, if you will, what the bad-faith case against sensitivity readers looks like

Who’s Making the Case?

For this first side of the argument, I’m pulling from a series of articles and op-eds I found on the subject. Allow me to introduce you to the three main detractors I’m quoting from we’ve got:

o Ryan Holiday: bestselling author of The Daily Stoic, Ego is the Enemy, former marketing director of American Apparel and former editor at the New York Observer. Holiday had what sounded like a positive unremarkable experience with a sensitivity reader and yet still found the need to write a long op-ed about why the practice shouldn’t exist in 2019

o Francine Prose: lauded American novelist, onetime PEN American Center president, and other fancy credentials-haver who wrote an op-ed for the New York Review of Books called “The Problem with Problematic” in 2017

o Lionel Shriver: author of the bestselling novel We Need to Talk About Kevin, professional provocateur, and patron saint of literary bad takes. Shriver wore a sombrero to give a keynote (to protest censorship?) and wrote a piece called “We Need to Talk About Sense and Sensitivity Readers” (wow) for The Guardian in 2017

As you can see from their impressive bios, all three of these detractors are high-profile and powerful in their own right. I wanted to begin with this who’s-who because as I’ll explain, the power dynamics here are everything.

So, what do these arguments look like?

It’s Censorship

“The sensitivity readers who get to decide which books are and are not okay to publish, and which words can be said and in what context are burning books—along with the fearful authors and publishers who empower them in their eagerness to avoid trouble.” –Holiday

It’s undeniable that the literary voices of marginalized communities have been underrepresented in the publishing world, but the lessons of history warn us about the dangers of censorship. Unless they are written about by members of a marginalized group, the harsh realities experienced by members of that group are dismissed as stereotypical, discouraging writers from every group from describing the world as it is, rather than the world we would like. – Prose

It’s not clear that authors are equally free to ignore the censoriousness of “sensitivity readers”, to whom some American editors are currently sending unpublished work for review. ...There’s a thin line between combing through manuscripts for anything potentially objectionable to particular subgroups and overt political censorship.–Shriver

The buzzword that came up again and again in these arguments was that this practice of hiring sensitivity readers somehow amounted to, or put us on a dangerous road to, censorship. Which, for anyone who needs a reminder, means the suppression or prohibitive works.

This argument deliberately misreads the power relationship here between publishers and sensitivity readers. Just as any other beta reader or consultant might, sensitivity readers wield no veto power and are generally paid between 250-500 per read. They do not hold any kind of gatekeeping role.

In the rare cases, publishers have pulled or delayed books because readers (as in consumers, not sensitivity readers) found them offensive, but that’s a different question (and one that still has nothing to do with censorship). In an era when self-publishing tools are widely available, you can easily get your book out into the world. Might it be less widely distributed? Seen as less credible? Sure! Sorry, book publishing is a business and things don’t get traditionally published for all kinds of reasons.

The bottom line here is that this is censorship like revoking your weird uncle’s invite to the family BBQ after he goes on a racist rant on Facebook is a violation of his first amendment rights

It’s PC Nonsense and Virtue Signaling

“Writers…are not hiring sensitivity readers because their primary concern is other people’s feelings, but because they don’t want to be the next victim of mob justice. Or because they are trying, consciously or otherwise, to advertise their progressive bona fides to their perceived audience.” – Holiday

“Moby-Dick might not exist if a sensitivity reader had objected to Melville’s depiction of the indigenous Queequeg,…should we “dismiss Madame Bovary because Flaubert lacked ‘lived experience’ of what it meant to be a restless provincial housewife”? – Prose

We are literally turning umbrage into an industry. When you reward touchiness, you only get more of it. Thus even after these manuscripts are purified, someone out there is bound to find more transgressions in the published version. – Shriver

I often find that people complaining about things being too PC just want to be able to punch down without consequence and that certainly seems to be the case here. Getting the details of a culture right rather than relying on tired tropes and stereotypes may be politically correct but it’s also just better writing. (I also find it funny that we continue to use the term “politically correct” when political discourse is such a mud-slinging dumpster fire, but I digress…) And as for virtue signaling: readers neither know nor care if you used a sensitivity reader, only whether you’ve written something that feels authentic and inclusive or hurtful and alienating.

I also find it notable that these writers use words like “tyranny, censorship, mob rule” to describe consultants who send thoughtful, carefully worded feedback which they can easily ignore, and/ or readers who on Twitter who are mad at them.

What a bunch of snowflakes, amirite?

It’s Inhibiting to Writers and will Make Us All Cowards

The other (and perhaps only?) real reason a writer might hire a sensitivity reader is to get permission to write their story. To be able to claim that they had received the green light from the Committee For The People’s Books. This is beyond cowardly and pathetic, and more offensive to the creation of art than any art that has ever offended. –Holiday

Literature will survive online social media bullying just as it has survived book burning and state censorship. One of the ugliest aspects of bullying is the way the aggressor finds easy targets and avoids the bigger, tougher challenges. But these attacks—and capitulations—may make it harder for us to champion the importance of the imagination at a time when we so urgently need to imagine a way to solve the larger crises that face us.—Prose

At the keyboard, unrelenting anguish about hurting other people’s feelings inhibits spontaneity and constipates creativity. The ghost of a stern reader gooning over one’s shoulder on the lookout for slights fosters authorial cowardice. Some writers terrified of giving offence will opt to concoct sanitized characters from “marginalized groups” who are universally above reproach. Others will retreat altogether from including characters with backgrounds different from their own, just to avoid the humiliation of having their hands slapped if they get anything “wrong.” –Shriver

I found this argument the most interesting because it is, at least on its face, an argument about creativity and craft. But to bring us back to the idea of “the liberal fear of the racist label”, it occurs to me that these writers are more afraid of being called a racist than of being racist. It’s not the validity of the concern, but the indignance at having to listen to it that bristles. No one likes to think they might be being accidentally racist, but if the idea of working with a sensitivity reader fills you with fear, that should tell you something

It bears repeating that this is all just a form of feedback and if you’re unable to hear feedback you don’t like and carry on, you are in the wrong profession as an author.

The idea that working with sensitivity readers or otherwise trying to write content that doesn’t punch down at a marginalized culture is somehow cowardly is absurd. It takes, as many of us are discovering, bravery to open ourselves up to authentic and difficult conversations around race, especially where it concerns our own beliefs or work.

Fantasy Debate Rebuttal

At the end of the day, you can write any old thing you want and Prose, Holiday, Shriver, and their numerous fellow detractors know this. People publish racist, sexist, offensive content all the time. They should be allowed to do so, but not without criticism.

Added up, these arguments are a smoke screen. These authors are using violent language and images to suggest that the people in power are actually the victims of something. Much like the dreaded “cancel culture” literary death by sensitivity exists chiefly in the imaginations of people who fear losing the privilege to say whatever they what with no consequences. Perhaps they long for the days when writers like Norman Mailer could run around saying things such as: “A little bit of rape is good for a man’s soul” and have his career continue unimpeded.

The truth is that the power balance in this relationship is firmly on the side of publishers and authors, especially high-profile ones like those I’ve quoted here. And to suggest that you are being censored or otherwise victimized when you’re in a position of power? That’s cowardly.

In Their Own Words:

Ryan Holiday: The Problem with Sensitivity Readers

Francine Prose: The Problem with Problematic

Lionel Shriver: We Need to Talk About Sense and Sensitivity Readers